Beyond the SoC: Seamless Integration of Virtual Platforms into Compound Simulations using the Functional Mock-Up Interface (FMI)

Author: Meik Schmidt

Full System Simulators, also known as Virtual Platforms (VPs), are truly remarkable, offering a host of benefits that are revolutionizing the development of complex systems. They enable early System-on-Chip (SoC) or microcontroller unit (MCU) software development without the need for physical prototypes, provide an efficient means to pinpoint hardware and software bugs, and are highly scalable and configurable, empowering streamlined hardware/software co-design workflows. Ultimately, VPs enhance the development process and the quality of the final product, all while significantly reducing development time and costs. It is no wonder their popularity and adoption across various industries have surged in recent years.

However, an SoC is rarely a standalone component; it is typically just one piece of a larger, intricate system. It constantly interacts with numerous other elements – mechanical parts, sensors, actuators, or even other SoCs – all working in concert to ensure the system behaves as intended. Consider a modern vehicle: it is a symphony of hundreds of mechanical parts controlled by dozens of electronic control units (ECUs), with countless sensors constantly monitoring its surroundings. Seamless interaction among these components is absolutely critical. A malfunction in this context could lead to substantial economic losses or, even worse, serious safety risks that endanger lives.

This is precisely why, in the early stages of development when real hardware is not yet available and VPs are our primary solution, it is crucial to simulate the overall system's behavior as accurately as possible. This proactive approach helps in catching costly bugs and malfunctions right from the start. And this is where Co-Simulation shines.

Co-simulation involves coupling multiple simulators, often from different vendors, to create a comprehensive simulation of an entire system. We previously explored this concept in a past blog post, where we also introduced Vector SIL Kit, an open-source library for connecting and simulating Software-in-the-Loop environments. We demonstrated how MachineWare's VPs can leverage this interface to integrate with various development tools. However, SIL Kit is not the only solution available.

Another widely adopted, open co-simulation standard for diverse simulators is the Functional Mock-Up Interface (FMI) [1]. Developed as a Modelica Association project, FMI benefits from contributions by major industry players such as Bosch, Dassault Systèmes, dSPACE, and many others. MachineWare's VPs actively support FMI, including advanced functionalities such as networked simulations. In this post, we will delve into how our VPs can be utilized with FMI, how to build a co-simulation with multiple VPs, and how to leverage various simulation tools that support the FMI standard.

FMI Explained: Core Concepts and Layered Standards

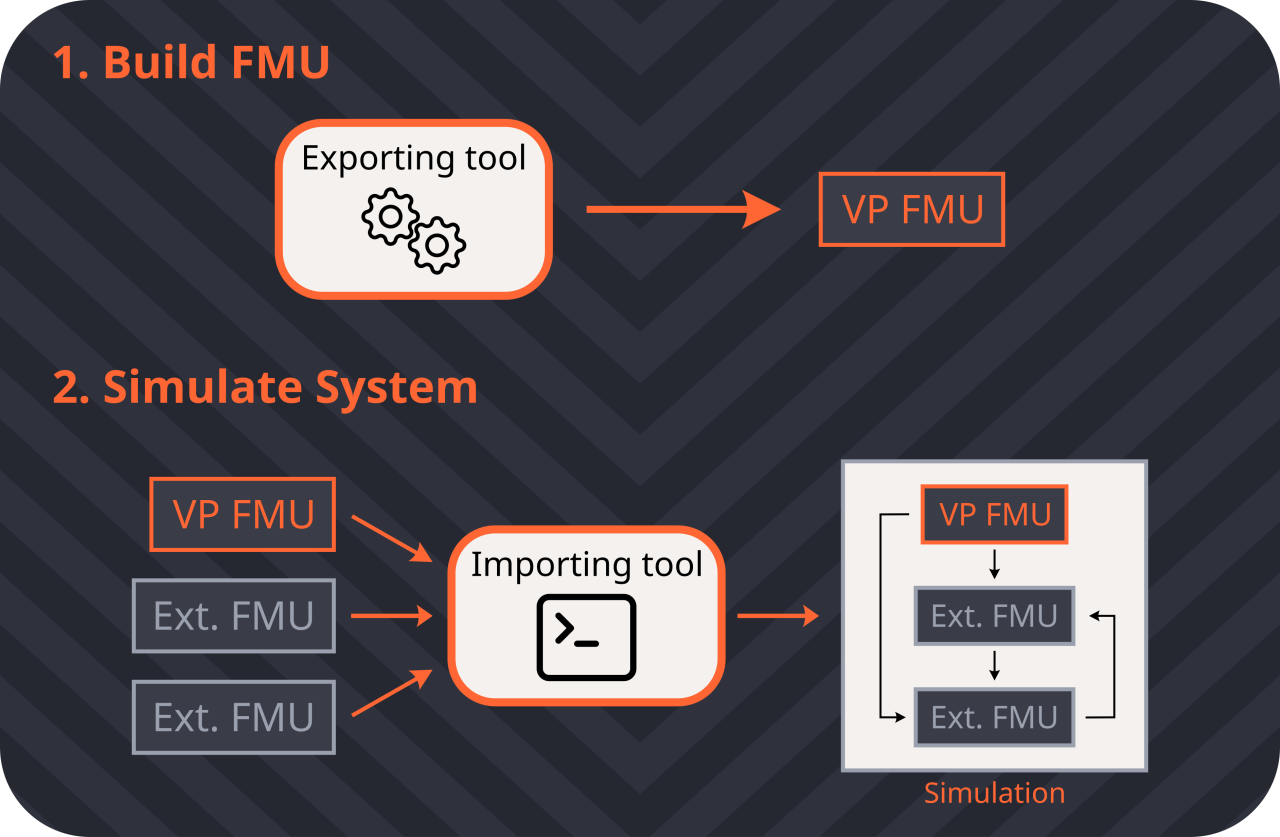

At its core, FMI defines how simulators are packaged, combined, and simulated. A simulator adhering to this standard is known as a Functional Mock-Up Unit (FMU). Multiple FMUs can be interconnected, communicating through a defined interface. The standard differentiates between two types of tools: exporting tools, which generate FMUs from existing simulators that comply with the standard; and importing tools, which import these FMUs, assemble the overall simulation, and finally run the entire system. Figure 1 visually illustrates this process.

At MachineWare we have developed an exporting tool that allows you to create FMUs out of MachineWare's VPs. This tool offers several compelling advantages, ensuring a more efficient and powerful simulation experience:

-

Lightweight and efficient: Our FMUs are incredibly lightweight, consuming minimal resources. This leads to faster and more efficient simulations within the importing tools.

-

Enhanced performance through workload distribution: Achieve significantly increased performance by distributing the workload of multiple Virtual Prototypes (VPs) across various machines within your networked compute cluster. This approach enables the effective utilization of computing resources from numerous workstations or the deployment of dedicated hardware for specialized VPs. For instance, substantial simulation performance improvements can be realized by running Arm VPs on Arm hosts, leveraging our cutting-edge Arm-on-Arm simulation technology [2].

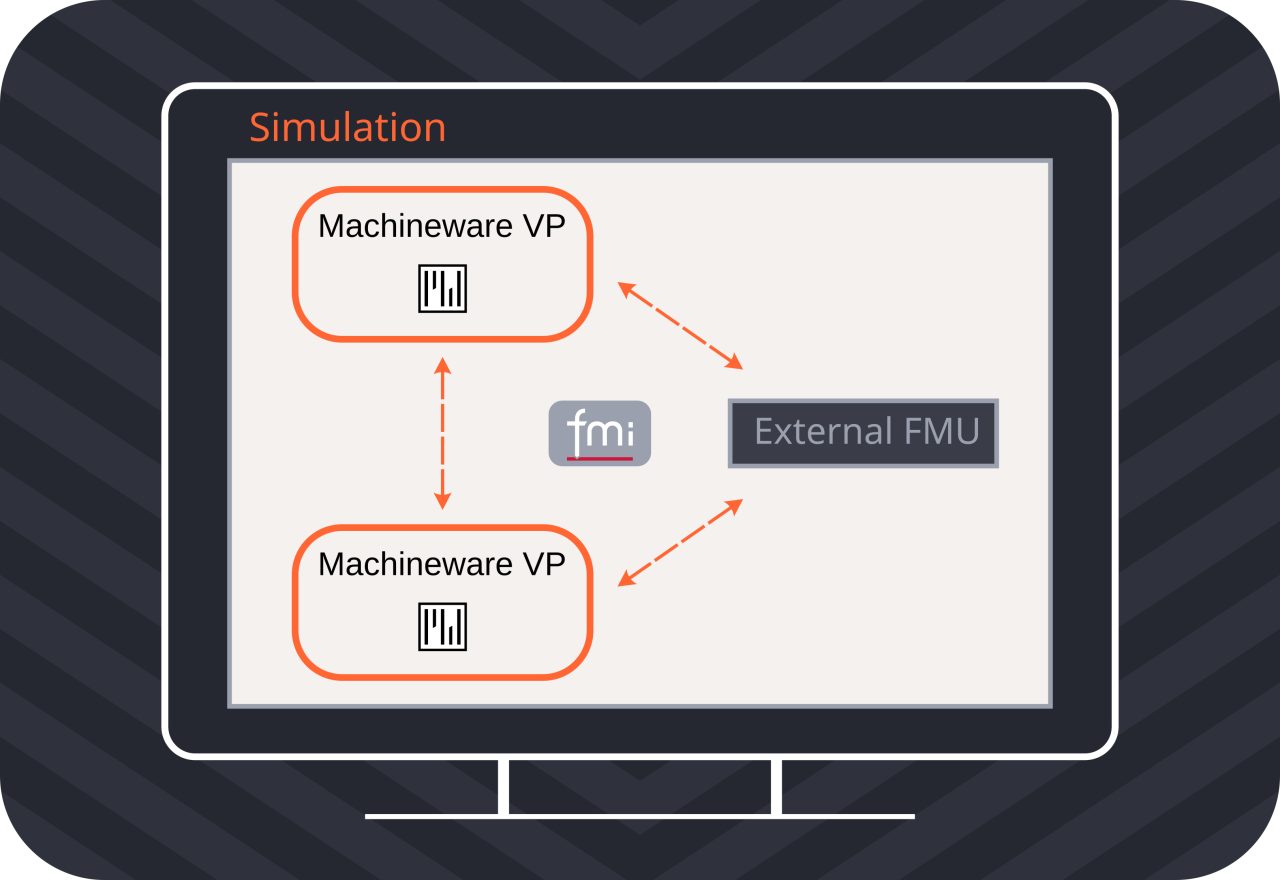

An exemplary simulation scenario involving two VPs and an external FMU is depicted in Figure 2.

Beyond its core standard, FMI also specifies new "Layered Standards" commencing with FMI version 3.0. These extensions are newly introduced and are currently undergoing active development. They enhance the base standard with additional functionalities, often tailored to a particular co-simulation domain or feature. One such Layered Standard supported by the MachineWare exporting tool is the 'FMI Layered Standard for Network Communication' (FMI LS-BUS). This adds the crucial ability to simulate communication between FMUs using popular network protocols such as CAN, Ethernet, FlexRay, and LIN. This makes the simulation of complex networked systems with multiple participants remarkably straightforward.

The following examples will demonstrate the ease with which FMUs can be generated from our VPs and seamlessly integrated into popular simulation tools.

First Steps in Co-Simulation: Single VP Simulation with FMPy

Our first example utilizes FMPy [3], a popular, open-source FMI importing tool that excels at loading and simulating single FMUs. The VP we will be working with is an Arm architecture simulator that boots a fully functional Linux operating system. After bootup is completed, a program is executed to monitor the temperature of a virtual sensor that is part of the VP. When the measured temperature crosses a predefined threshold, the program will then set or unset a GPIO pin to signal this information to another system (Schmitt-Trigger [4]). FMPy will control the input temperature values via the FMI interface and monitor the corresponding GPIO output.

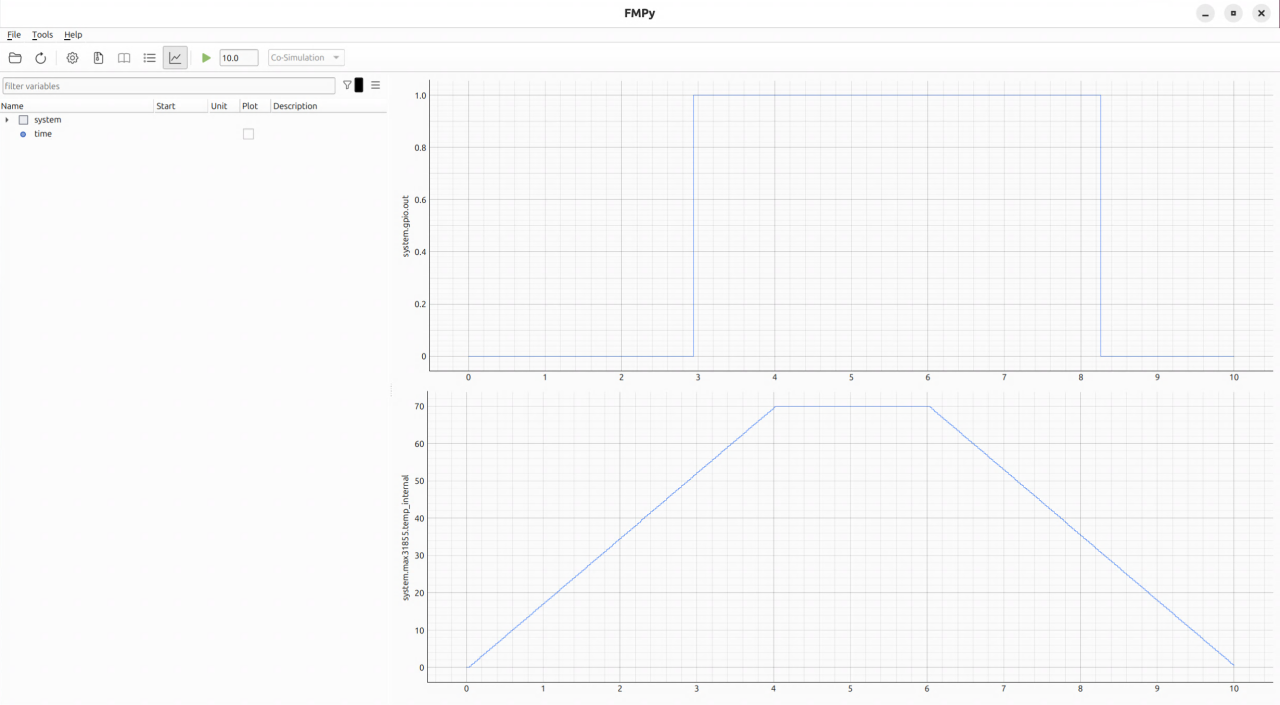

To achieve this, we first need to build our FMU. This involves providing configuration options, such as specifying which VP’s variables and properties we want to access via FMI. With this information, our exporting tool generates an FMU that can be directly loaded by an importing tool such as FMPy. Once the VP is manually started, the simulation can commence with our specified input values. The simulation results, clearly shown in Screenshot 1, demonstrate that the VP behaves exactly as expected. The bottom graph displays the temperature curve of the virtual temperature sensor, while the top line indicates the corresponding value of the GPIO output pin. As the temperature rises above 50°C, the GPIO pin is set, and it remains set until the temperature drops below 30°C, at which point it is unset again. This successfully proves the intended Schmitt-trigger functionality.

While simulating single FMUs is useful for verifying individual system behavior, the true power of FMI lies in its ability to handle more complex scenarios involving multiple systems. For this reason, we will now explore a more realistic simulation example using the dSPACE VEOS simulator.

Advanced Co-Simulation: Networked VPs with FMI-LS-BUS and dSPACE VEOS

In this example, we will connect two instances of our Arm VP via an FMI-based CAN network. Since network communication is not part of the basic FMI standard, the FMI-LS-BUS Layered Standard was developed specifically for this purpose [5]. This extension to the FMI standard is relatively new and still undergoing active development. Nevertheless, dSPACE's VEOS simulation platform already offers native support for this technology. Since the MachineWare exporting tool also supports FMI for network communication, VEOS can be used to create a compound simulation involving multiple VPs connected through a virtual FMI-based CAN bus.

To effectively showcase the advanced capabilities of FMI-LS-BUS for compound networked simulations, we build a realistic demonstration scenario, which is based on the example discussed in one of our previous blog posts. In this adjusted setup, we leverage two Arm Virtual Prototypes, acting as a rain sensor and a windshield wiper vECU, each running a full Linux operating system.

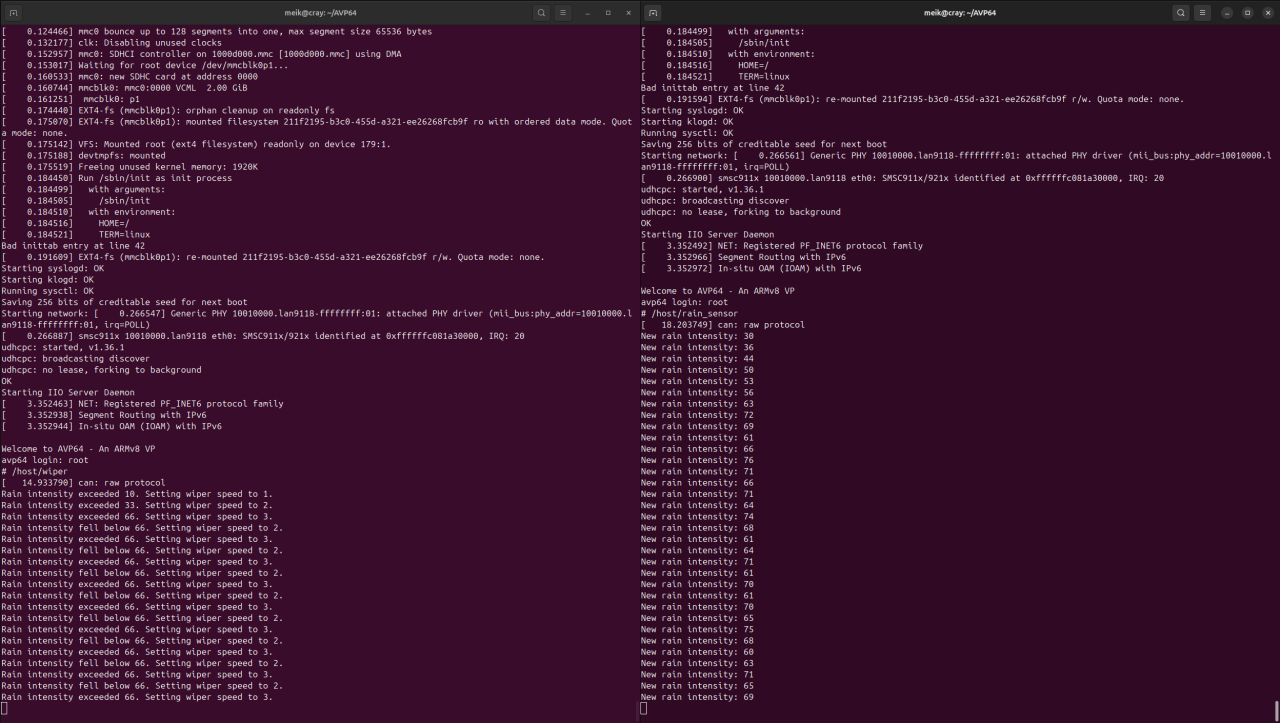

Once booted, these VPs execute distinct user-space processes that seamlessly exchange relevant CAN messages over the virtual bus. One VP emulates the behavior of the rain sensor, transmitting real-time rain intensity values to the virtual CAN bus. Concurrently, the second VP acts as an vECU of a responsive car windshield wiper system, dynamically adjusting its speed in response to the received rain intensities from the rain sensor. The behavior of both VPs is clearly displayed in Screenshot 2, where the left terminal shows the windshield wiper VP's speed adjustments and the right terminal showcases the rain sensor VP's continuous output.

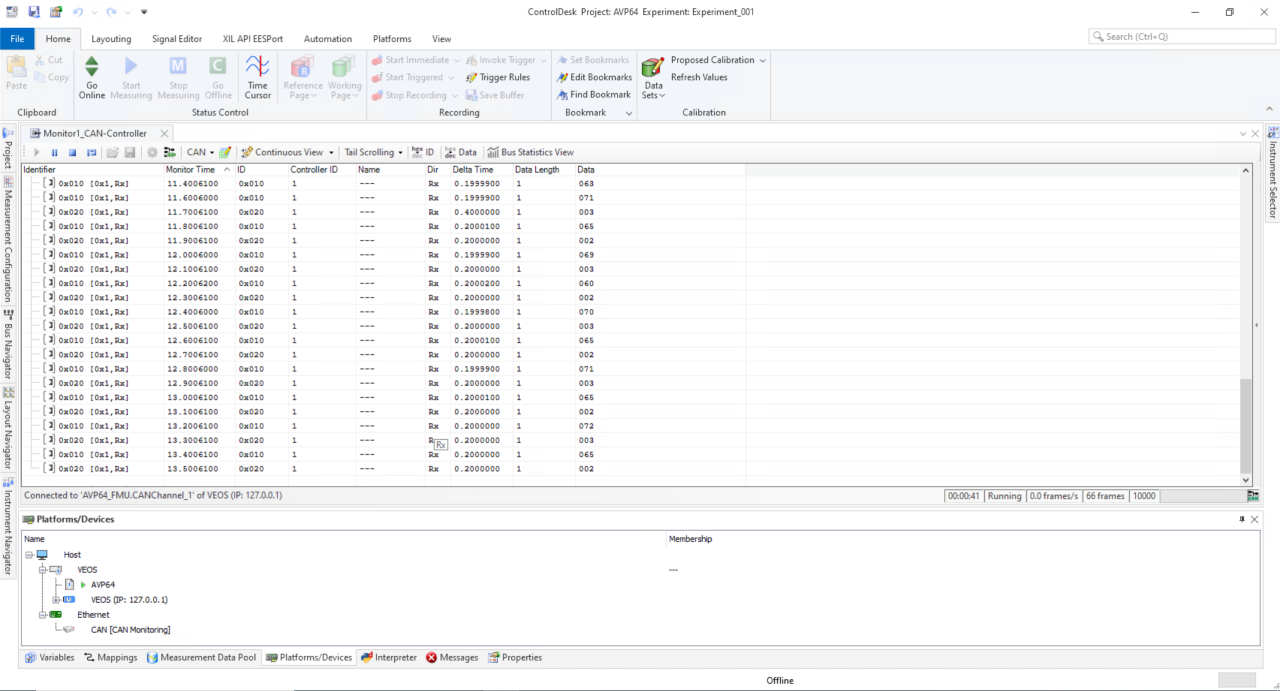

To provide extensive insight and control, we integrate dSPACE's ControlDesk application, enabling comprehensive, real-time monitoring of the virtual CAN bus throughout the simulation. As clearly illustrated in Screenshot 3, ControlDesk offers detailed information on all transmitted frames, empowering you to display and analyze critical bus traffic with precision and ease. This level of transparency is invaluable for rapid debugging, thorough validation, and fine-tuning the performance of networked systems.

This example clearly demonstrates the seamless integration of MachineWare's VPs into complex networked simulations through the powerful FMI standard. This capability is invaluable for validating distributed software architectures, testing communication protocols under various load conditions, and performing early integration tests for systems with multiple interacting ECUs or processing units. It allows developers to identify and resolve potential communication bottlenecks or data synchronization issues long before committing to physical prototypes, thereby saving significant time and resources in the overall development cycle.

Conclusion

The FMI standard is a vital industry standard, developed to simplify the common task of coupling diverse simulation tools across various industries. It streamlines the design and verification of complex products and systems. By integrating MachineWare's VPs into such Co-Simulation environments, developers can significantly enhance their development workflow with highly accurate and incredibly efficient simulators for early-stage software development. Since target software can run unmodified on our VPs, its impact on the entire system can be analyzed and evaluated long before physical prototypes are even available. This proactive approach leads to earlier bug detection, more reliable and secure software, and ultimately, superior final products.